- Home

- KNMA, Saket, Delhi

KNMA, Saket, Delhi

Convergence

A Panorama of Photography’s French Connections in India

28 April 2022 - 30 June 2022

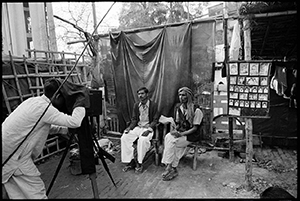

An exhibition on photography will be opening simultaneously at KNMA, Saket. Produced by intrepid travellers, writers, journalists, photographers and artists, the exhibits will span the colonial, modern and postcolonial periods of subcontinental history from the mid-nineteenth-century to the 1970s. It will feature works of notable French photographers over broad spans of time, such as Louis-Théophile Marie Rousselet; a French traveller in India during the 1860s who met India’s first photographer king, Sawai Ram Singh II in Jaipur. Marc Riboud a celebrated French photojournalist who worked for Paris-based Magnum Photos from 1953-78 and travelled all around Asia in the 50s along with the works of many other modern European masters such as Denis Brihat, Paul Almasy, Edward Miller and Bernard Pierre Wolff among others.

Convergence

A Panorama of Photography’s French Connections in India

28 April 2022 to 30 June 2022

KNMA Saket

An exhibition on photography will be opening simultaneously at KNMA, Saket. Produced by intrepid travellers, writers, journalists, photographers and artists, the exhibits will span the colonial, modern and postcolonial periods of subcontinental history from the mid-nineteenth-century to the 1970s. It will feature works of notable French photographers over broad spans of time, such as Louis-Théophile Marie Rousselet; a French traveller in India during the 1860s who met India’s first photographer king, Sawai Ram Singh II in Jaipur. Marc Riboud a celebrated French photojournalist who worked for Paris-based Magnum Photos from 1953-78 and travelled all around Asia in the 50s along with the works of many other modern European masters such as Denis Brihat, Paul Almasy, Edward Miller and Bernard Pierre Wolff among others.

The exhibition has been touring different cities across India, including Bengaluru and Ahmedabad and will be exhibited in Chennai, Kolkata and Mumbai in the coming months. We are glad to announce that the original photographs will being shown at KNMA, Saket, with Gelatin silver prints (modern)by Marc Riboud, Gelatin silver bromide prints by Paul Almasy and group portraits in front of painted studio settings. Photogravure on paper mount on card board by unidentified photographers will be amongst other in the display.

Other Exhibitions

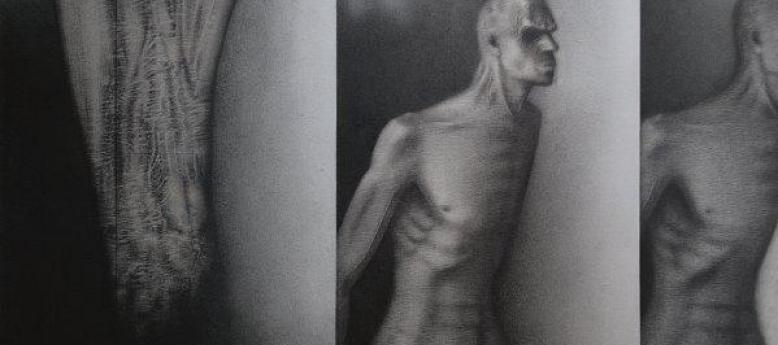

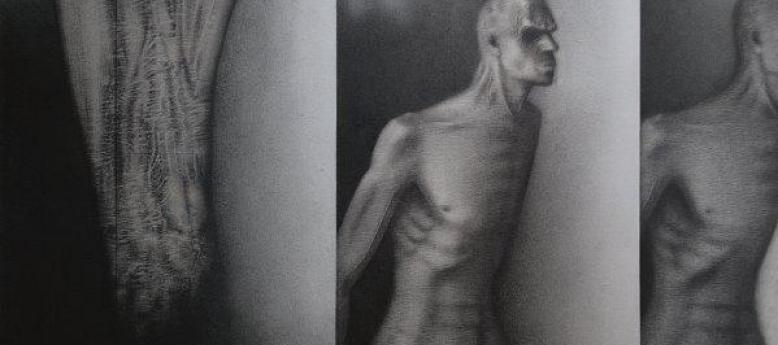

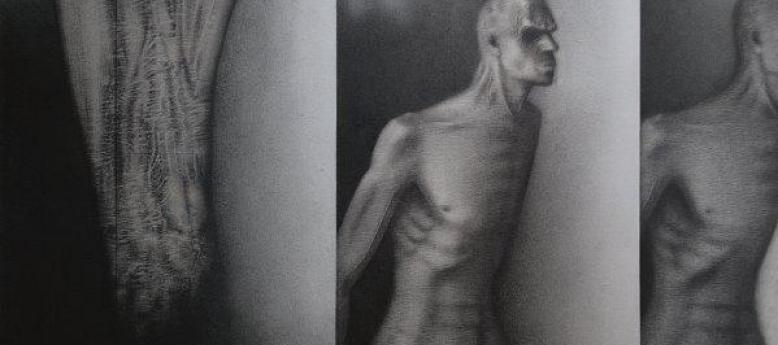

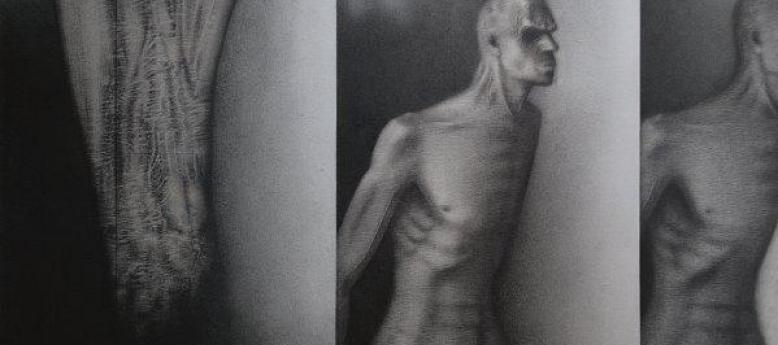

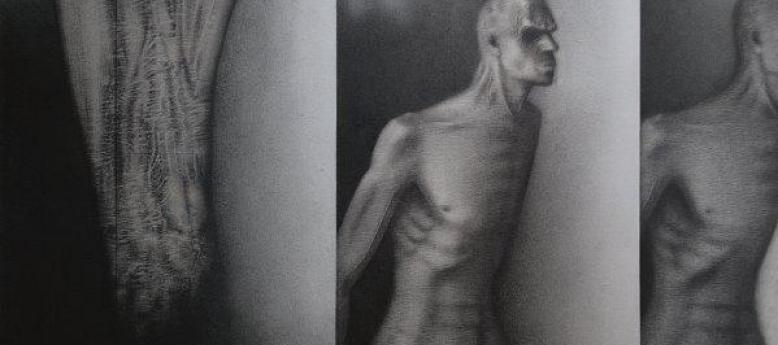

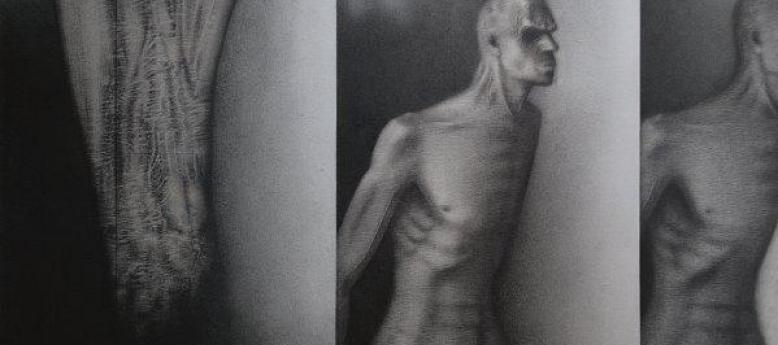

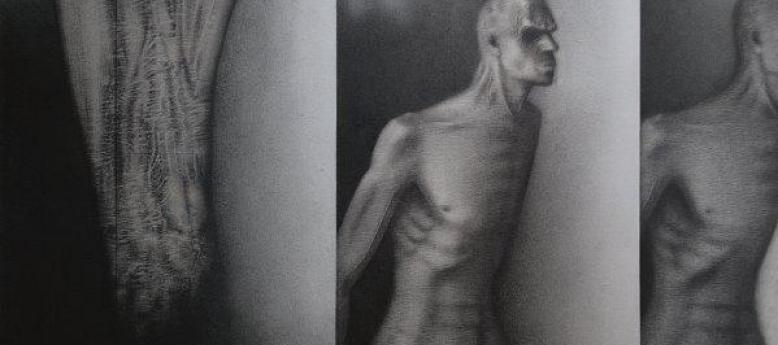

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

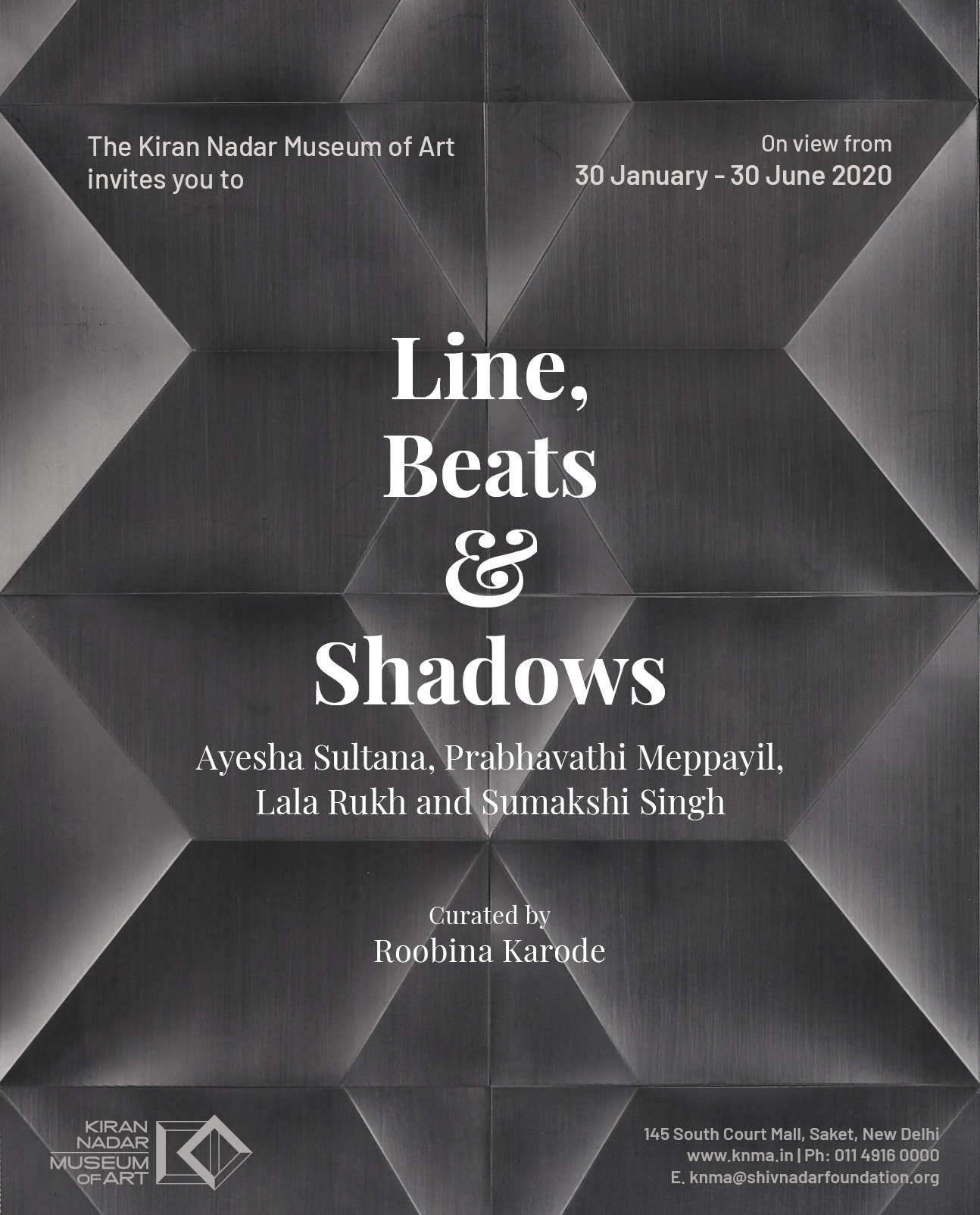

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

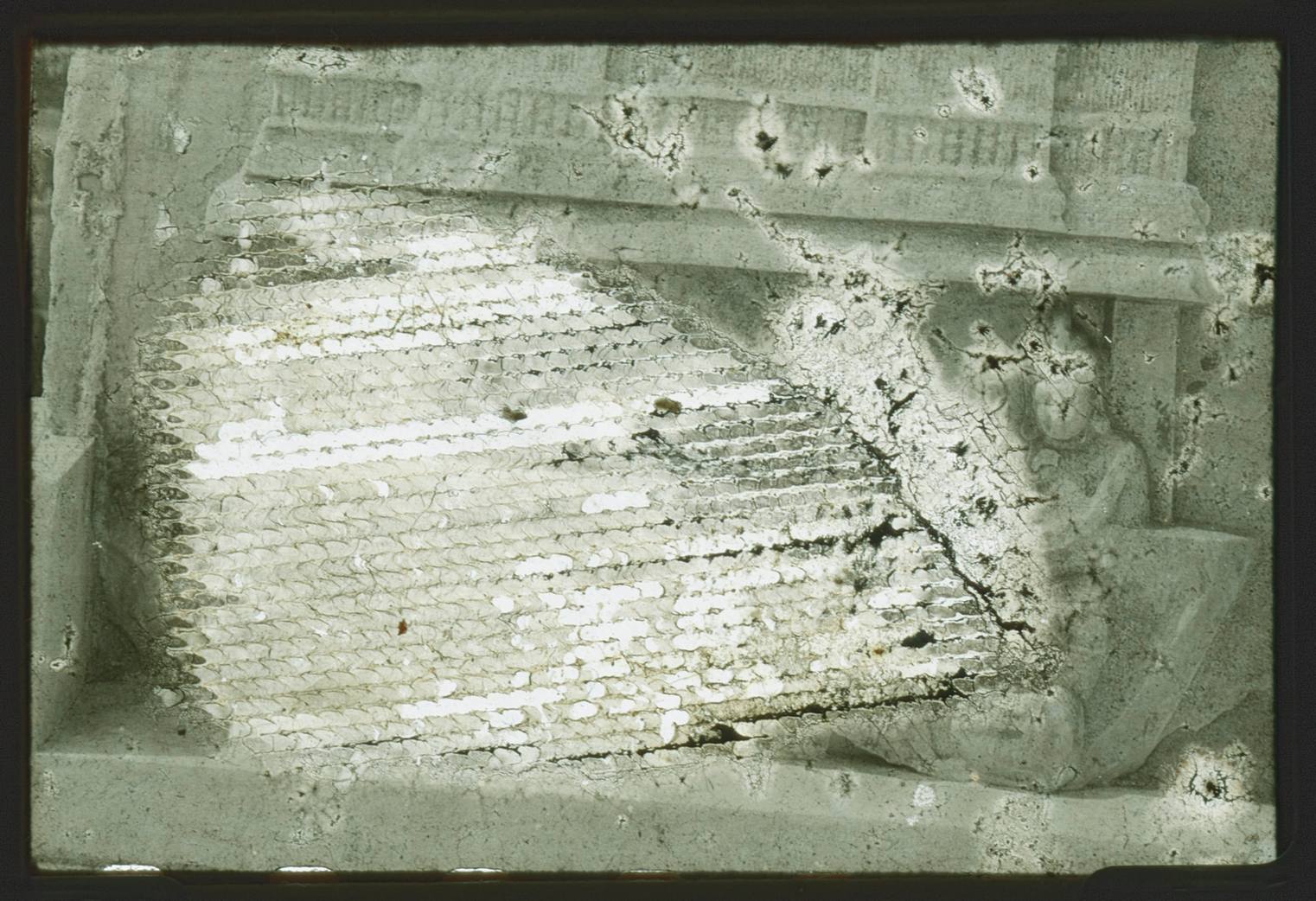

Somnath Hore | Birth of a White Rose

28 April 2022 - 30 September 2022

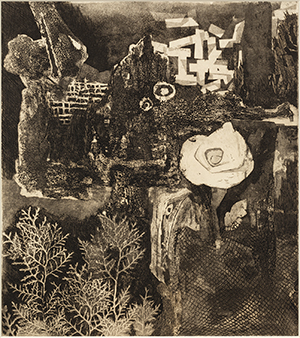

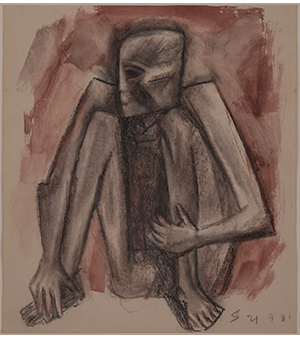

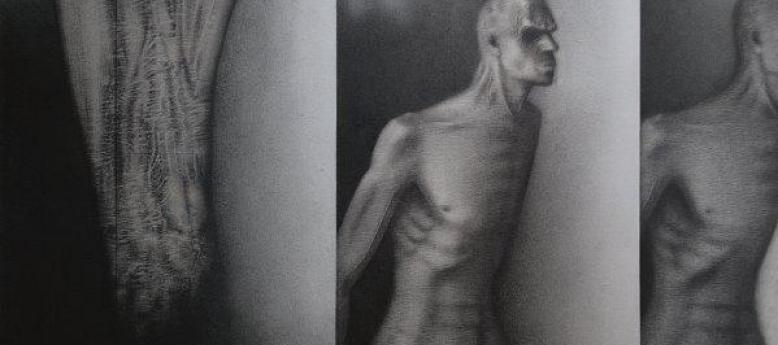

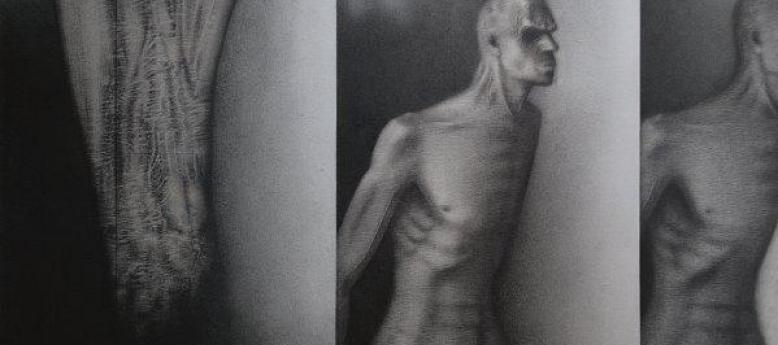

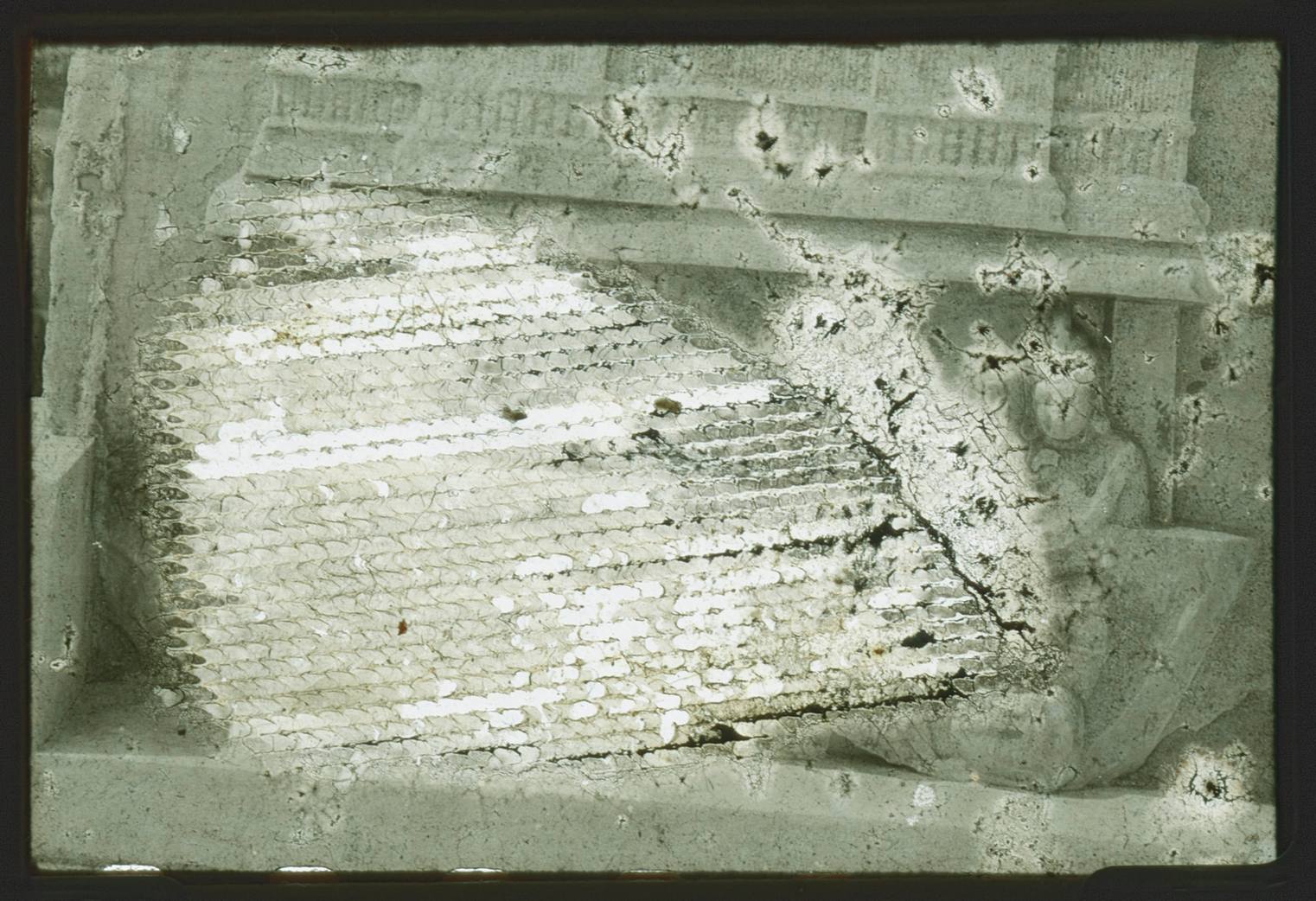

Somnath Hore (1921- 2006), or Somnath da as his students and appraisers admiringly addressed him, was born in Barama village in Chittagong, in undivided Bengal (present Bangladesh). His life and art exemplified an artistic practice that drew from a collective ideology of existential amelioration, equality and empathy, all in tandem with Hore’s own personal philosophy expressed through his writings and interviews.

Somnath Hore | Birth of a White Rose

28 April 2022 to 30 June 2022

KNMA Saket

Somnath Hore (1921- 2006), or Somnath da as his students and appraisers admiringly addressed him, was born in Barama village in Chittagong, in undivided Bengal (present Bangladesh). His life and art exemplified an artistic practice that drew from a collective ideology of existential amelioration, equality and empathy, all in tandem with Hore’s own personal philosophy expressed through his writings and interviews.

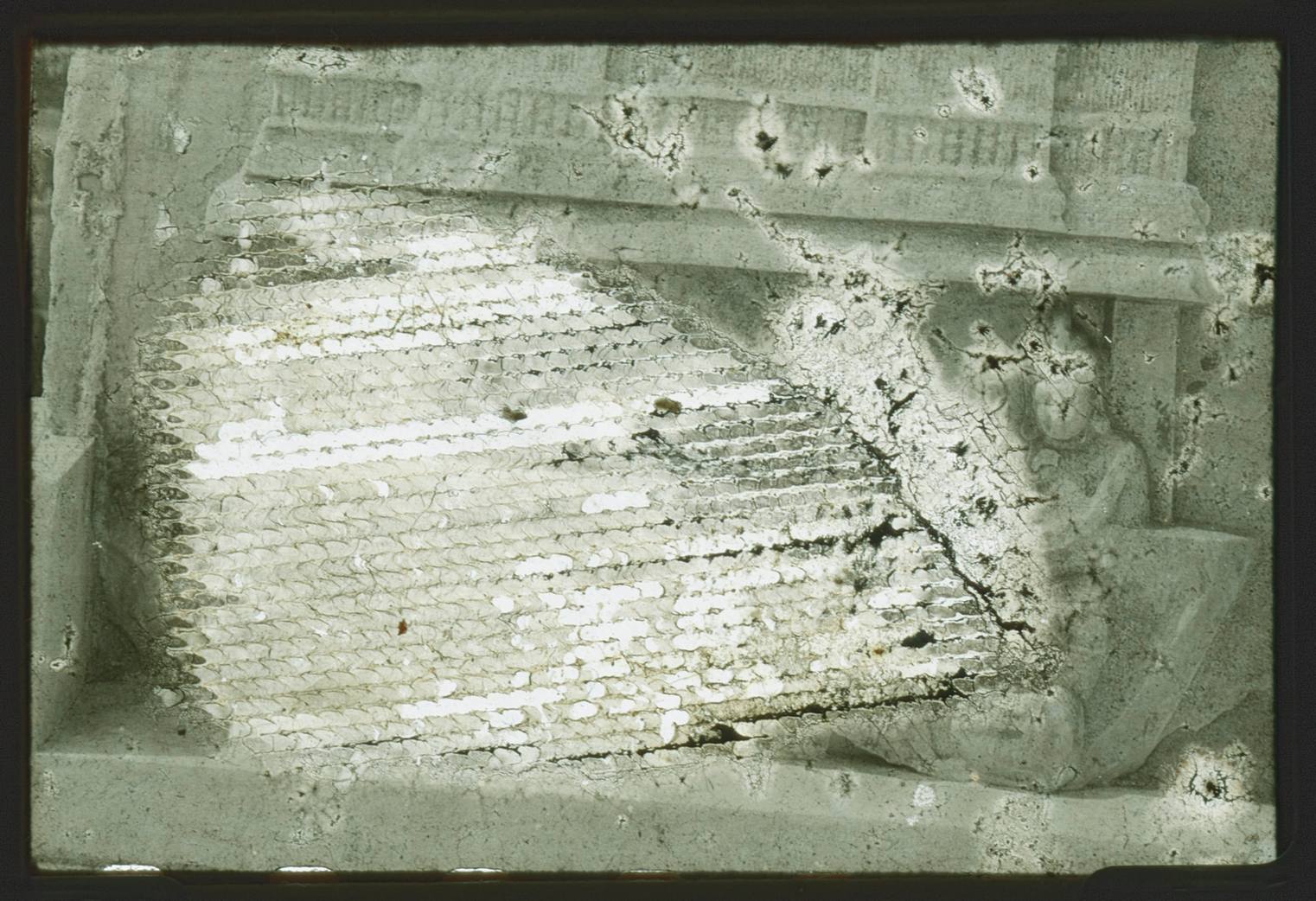

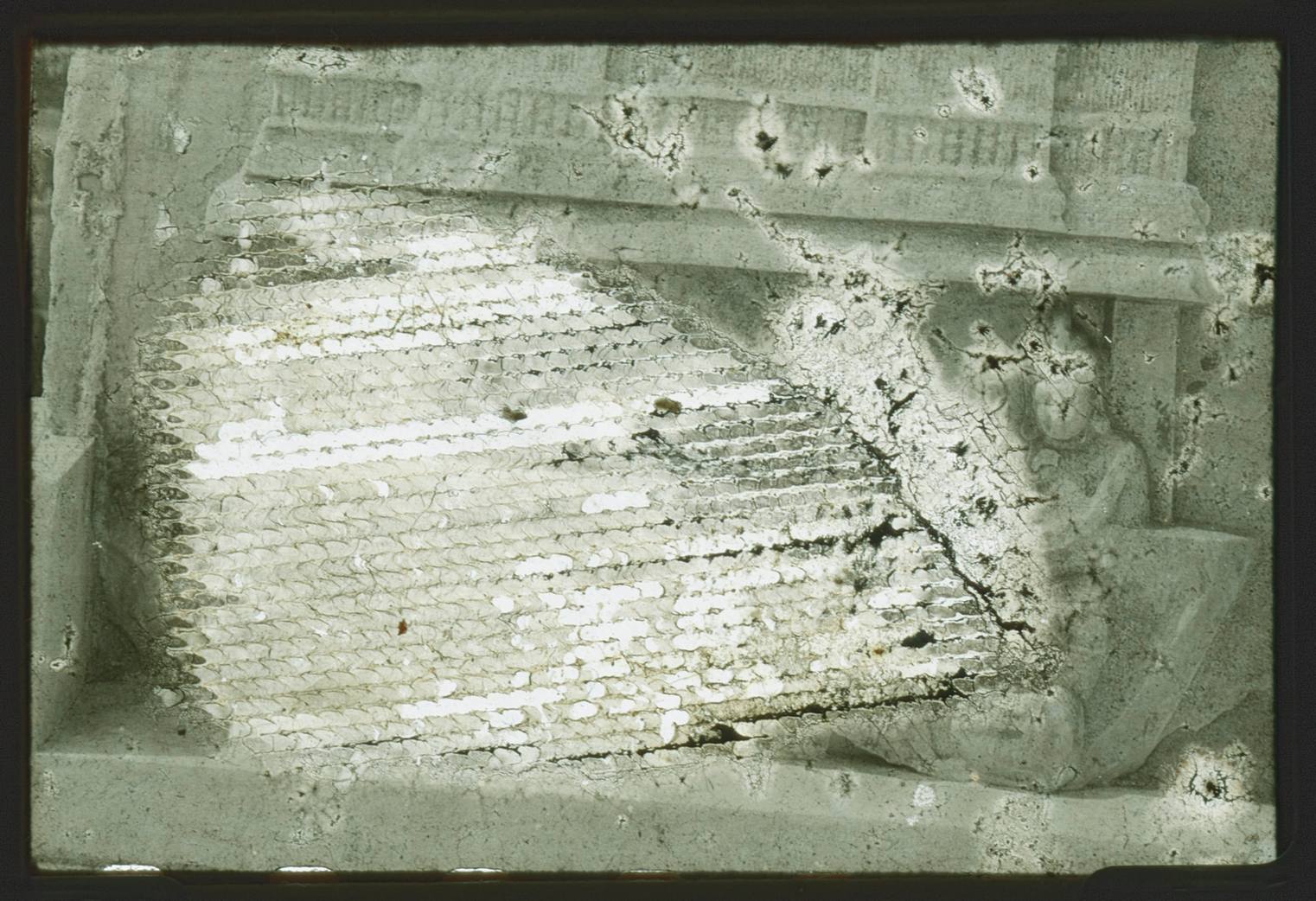

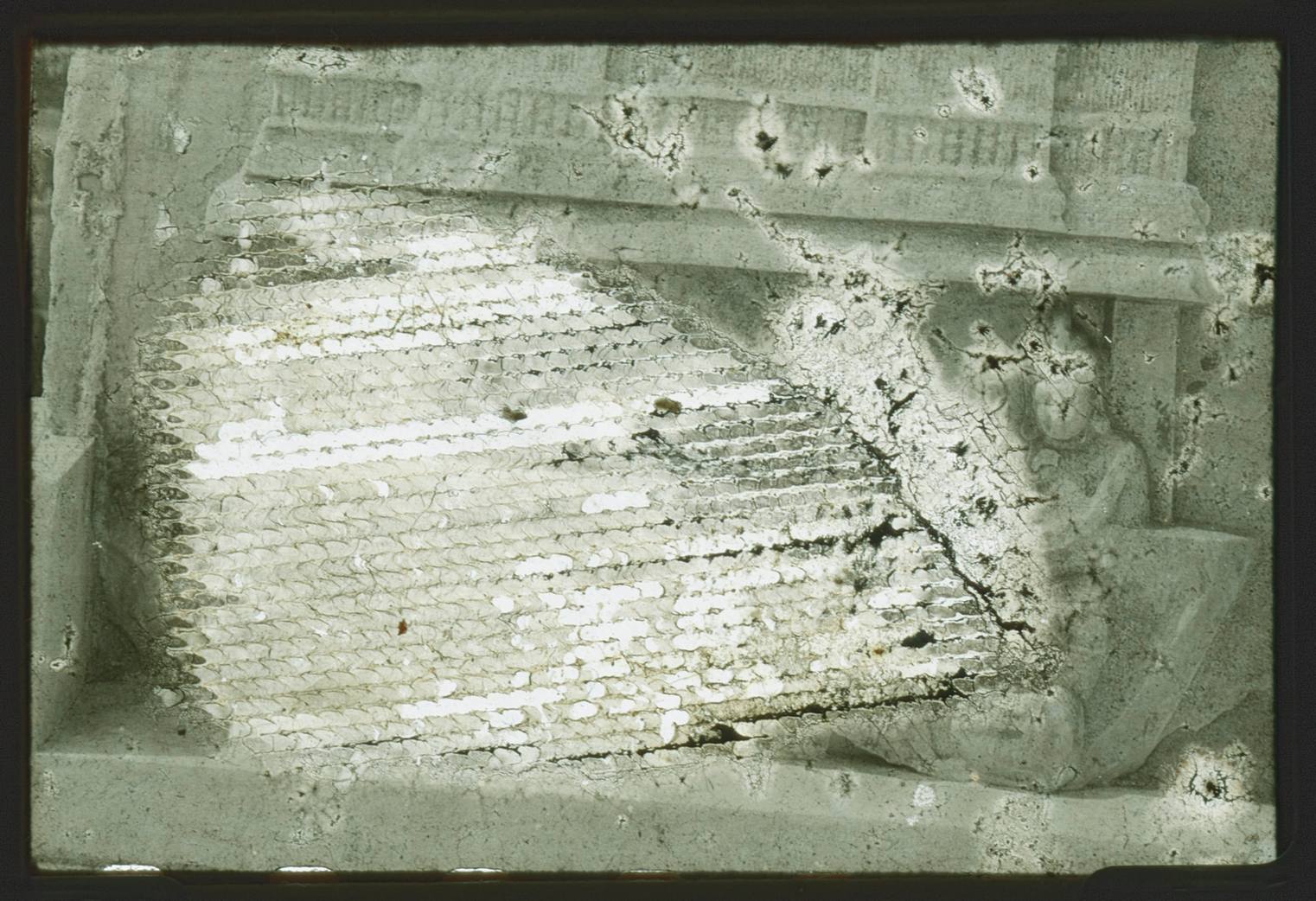

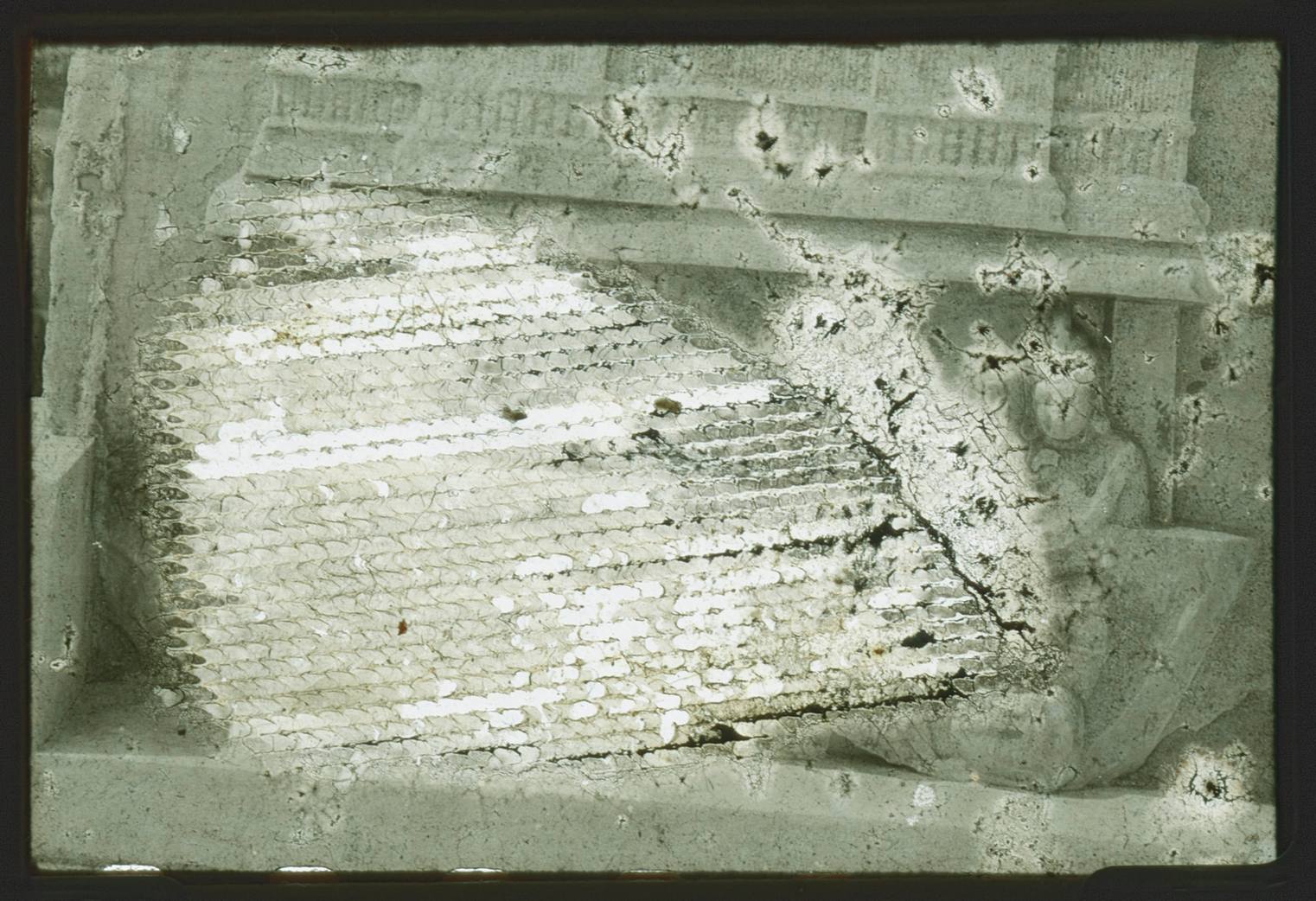

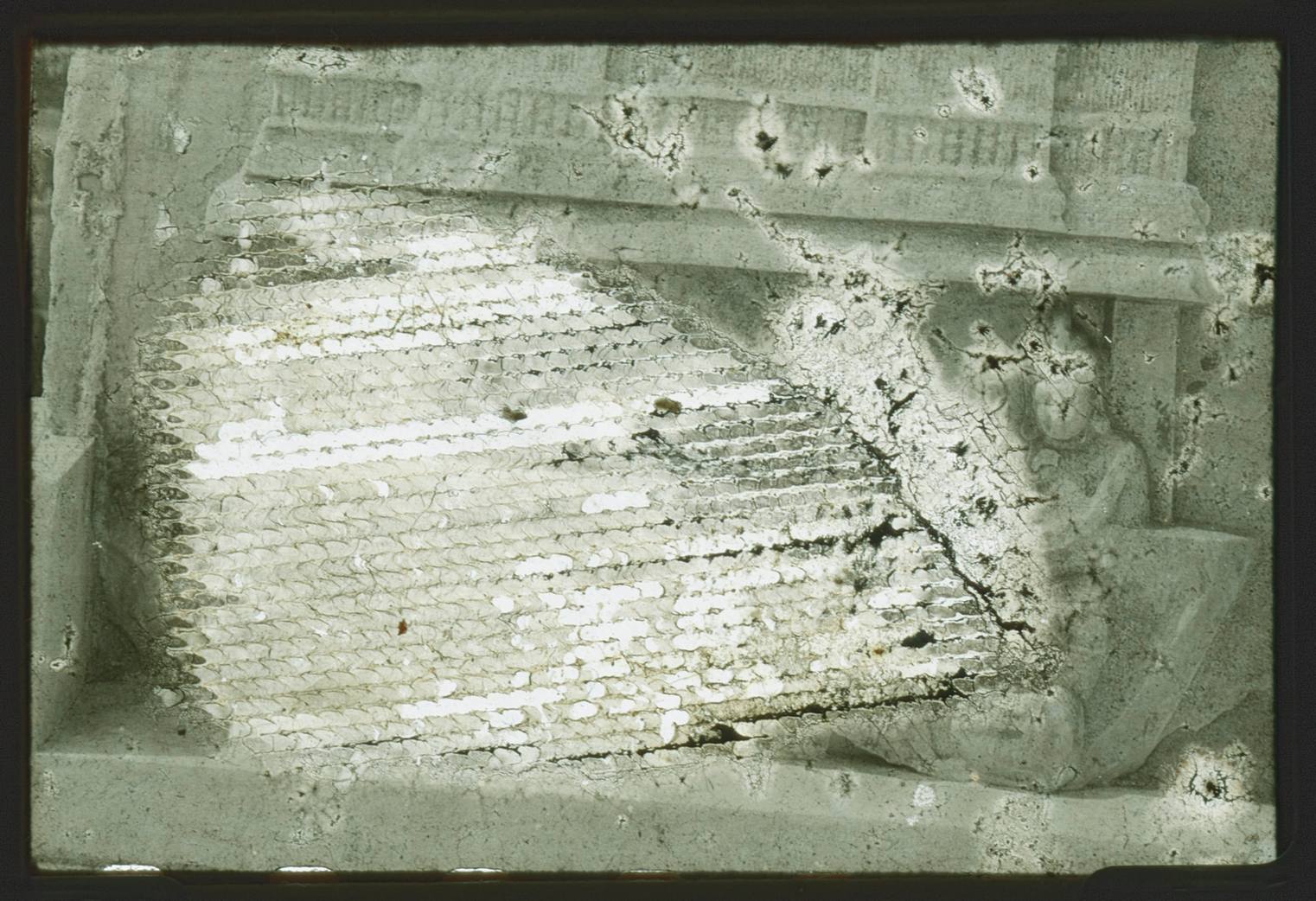

The title of the exhibition drawn from one of Somanath’s iconic work ‘Birth of a White Rose’ (which received the Lalit Kala Akademi National Award in 1962). It refers to the curatorial intention of exploring a practice which transcended fragile contours of the corporeal and the troubled geographical terrains, and touched the realm of the abstract by embracing the figural. This aspect of in-betweenness of the body and the spirit is central to the exhibition’s curatorial proposition.

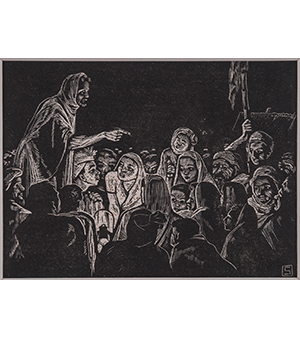

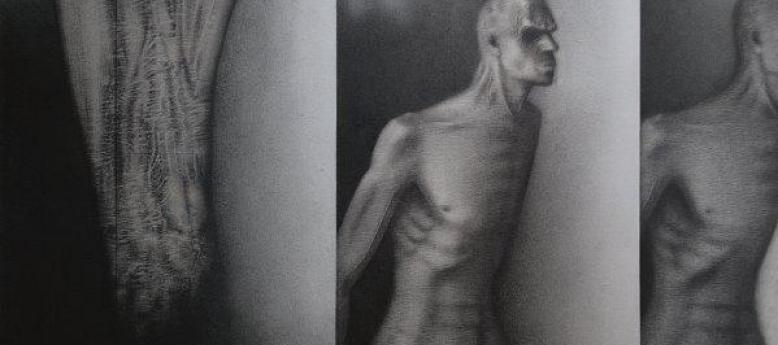

A subcontinental match to Oskar Kokoschka or Käthe Kollwitz in artistic spirit and aesthetic idioms, Somnath internalised the crux of socialist values and transmuted them into a visual language—lucid, tangible and comprehensible to the masses. His works from various phases in diverse mediums were markers of the volatile times that the artist lived through. Chronicling societal dynamics by observing class conflicts and the violence around, they were contemporary to a transformative cultural juncture when literature, theatre, cinema and other creative expressions in Bengal were touching crescendo. Interrelations between lands, people and ideas were undergoing phenomenal conversions prompted by the manmade Bengal Famine of 1943, the peasant unrest of the mid-1940s, the Partition in 1947 and migration from the east of Bengal, and the two-decade long Vietnam War ending in the 1970s. Radical changes in artistic language responding to these situations were seen in the works of Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad, along with the works originating from the Calcutta Group. Distancing from the European academicism and the lyricism of Bengal and Santiniketan schools, these artists became attentive to the power of figurative representation and social realism. Somnath, a student of Abedin and friend of Chittaprosad, shaped his own visual lexicon, with time attaining a stylistic singularity. Artistic responses to these situations were seen in the works of communist artists Zainul Abedin and Chittaprosad, who were Somnath’s teacher and fellow-activist respectively. While partaking in rescue operations as a communist activist in the early-1940s, Somnath tried to capture the daily struggles for survival and dignity in fast-paced documentative sketches.Some of these drawings were published in the Communist Party magazine Janajuddha (People’s War), along with his diary entries and sketches of the Tebhaga movement in North Bengal Rapid lines and expressive nuances of the faces with anatomical details, depicting intense moments of mass gatherings, establish his unique style from this phase. Many of these drawings were transferred to woodcut prints in the 1950s.

Eventually by the mid-1950s after estranging from active political involvement and the art of socialist realism, Somnath moved to New Delhi, and subsequently to Santiniketan. An empathetic pedagogue and convinced modernist by now, Somnath inspired generations of students and artists while heading the department of printmaking at the Delhi Polytechnic in 1958, and subsequently the department of Graphics, Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan, West Bengal.

Somnath’s etchings and engravings from the 1960s such as Refugee Family, with weary sorrowful expression, reminds his personal experiences and the collective pathos of Partition of the country. The recurring question of care and compassion or perhaps the lack of the same in society propelled him to revisit the theme of ‘Mother and child’ time and again through various mediums, sometimes through the gleam of bronze and at others through the strong rapid lines drawn or etched.

Renditions in a wide range of mediums such as oil on canvases, drawings in watercolour and crayons, different methods and techniques of printmaking and bronze cast sculptures, the exhibition will showcase a selection of more that hundred works. Metal plates that he used for taking prints, diaries, lithographs, woodcuts and etchings will be some of the lures of the show.

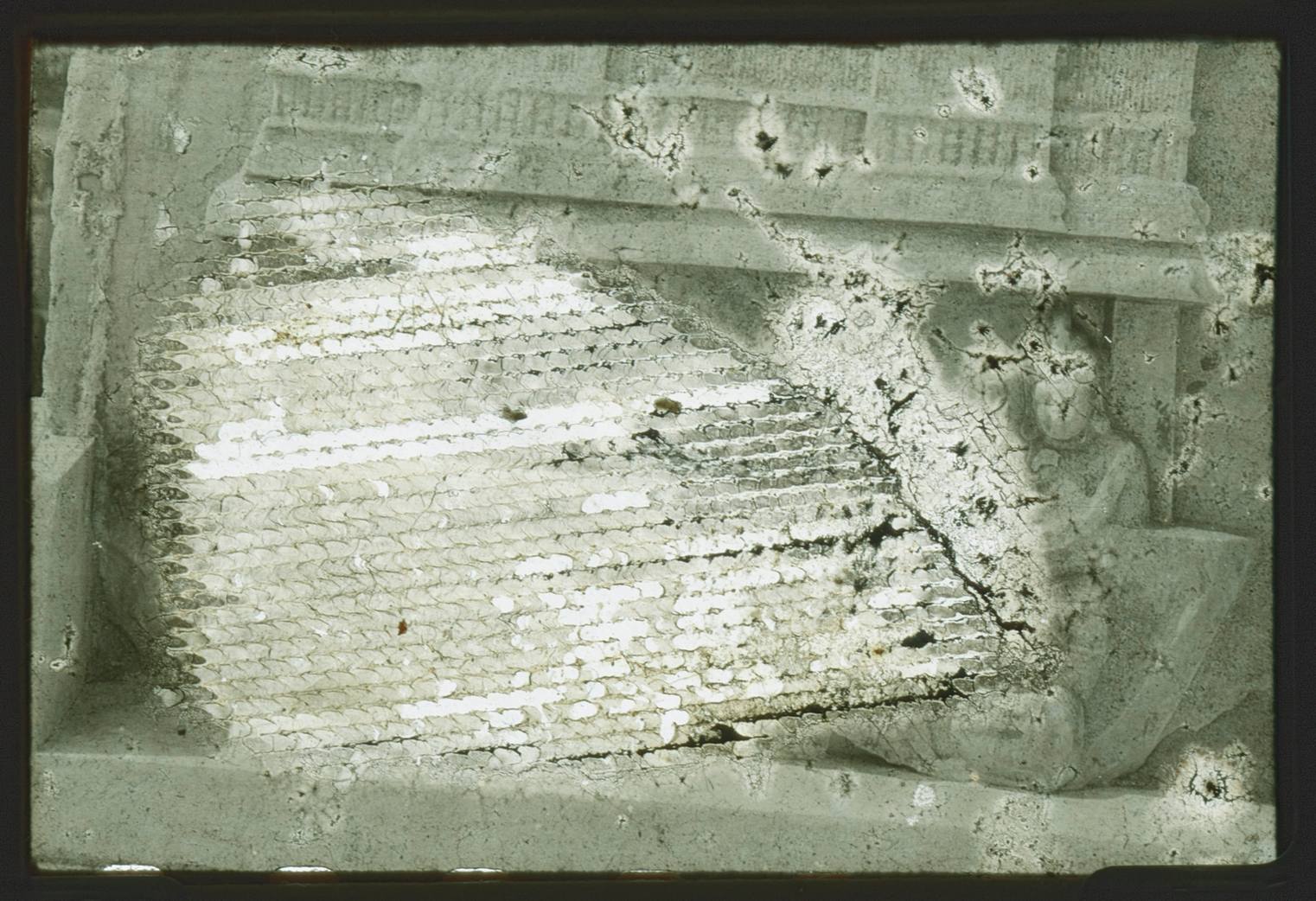

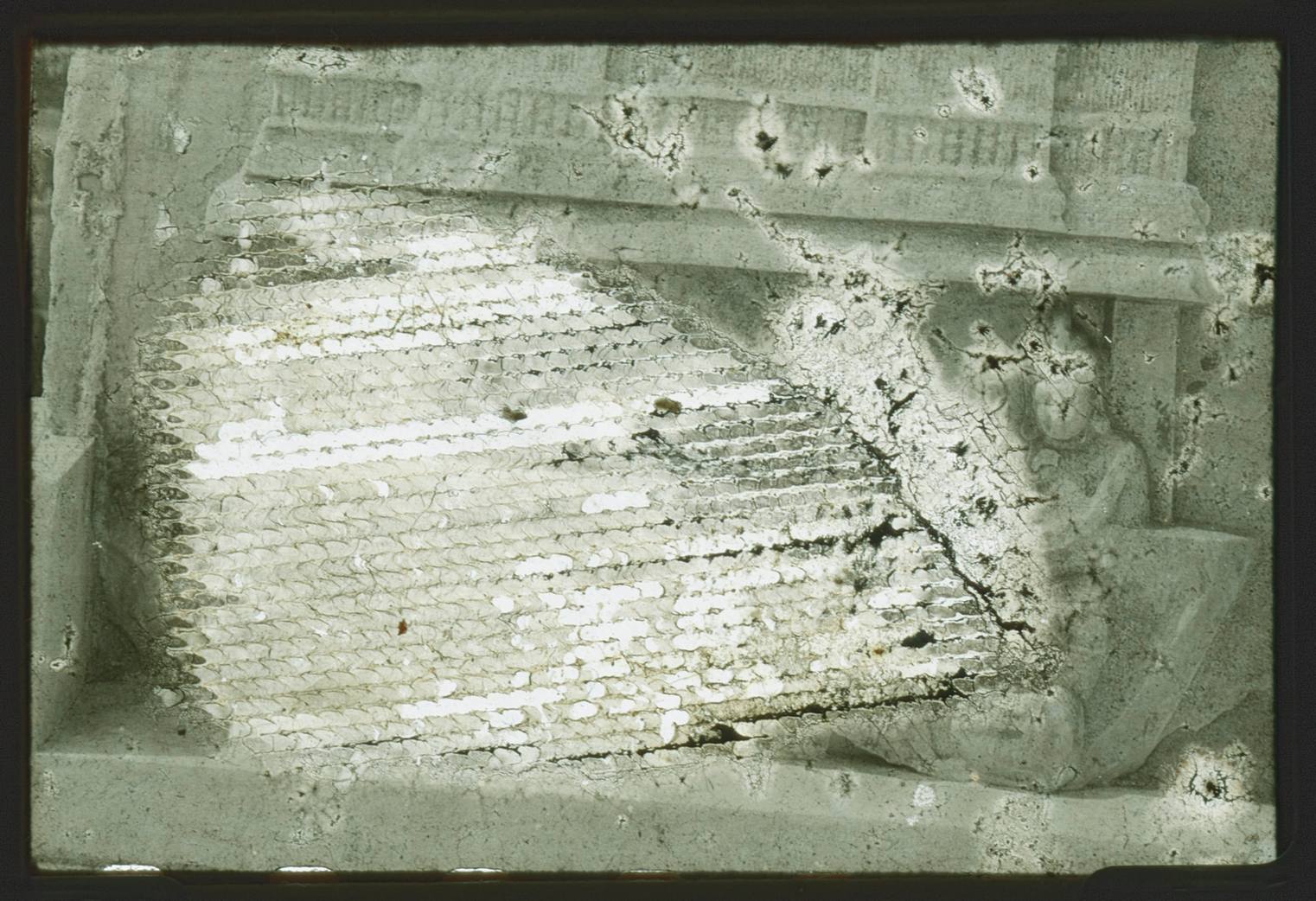

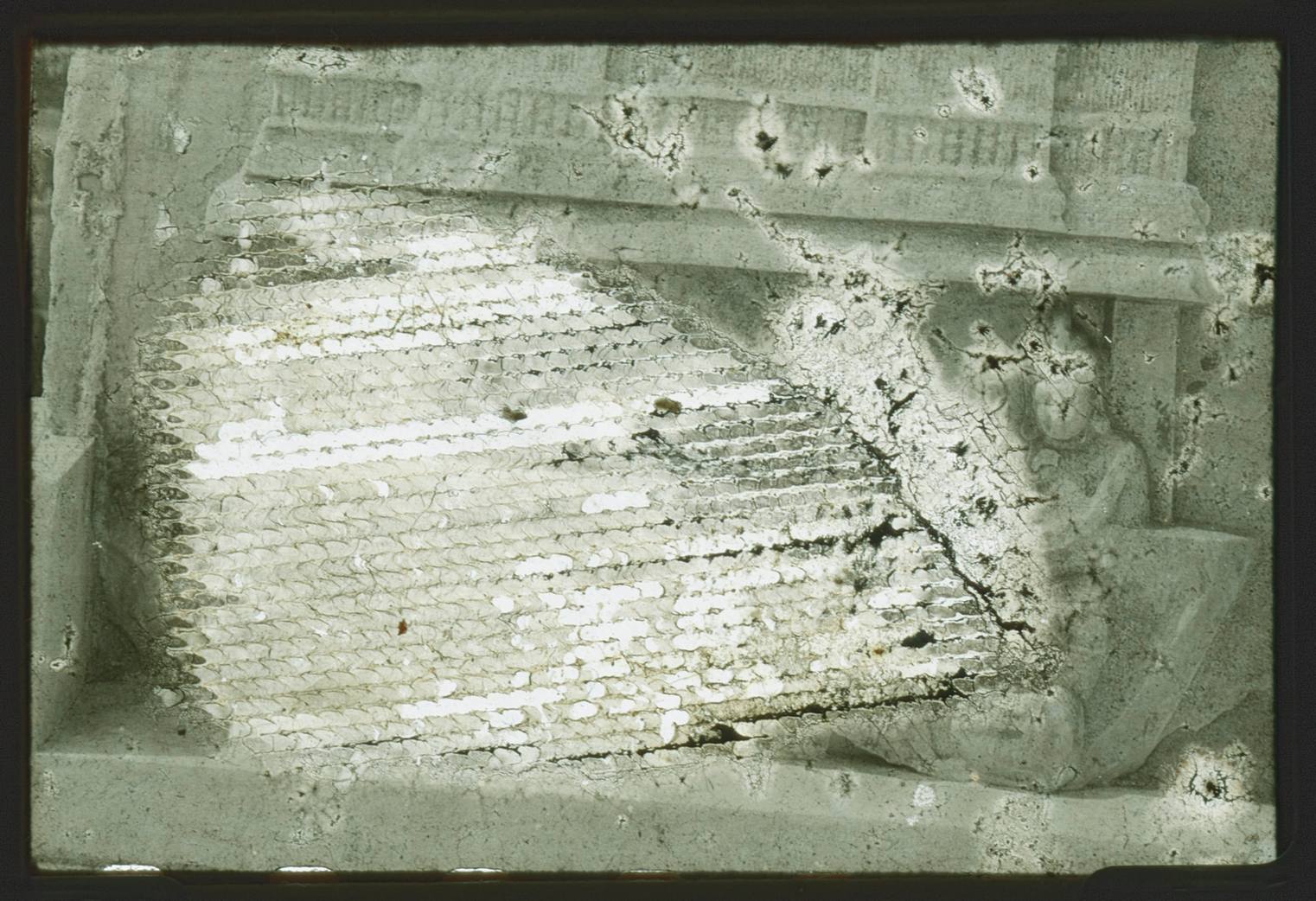

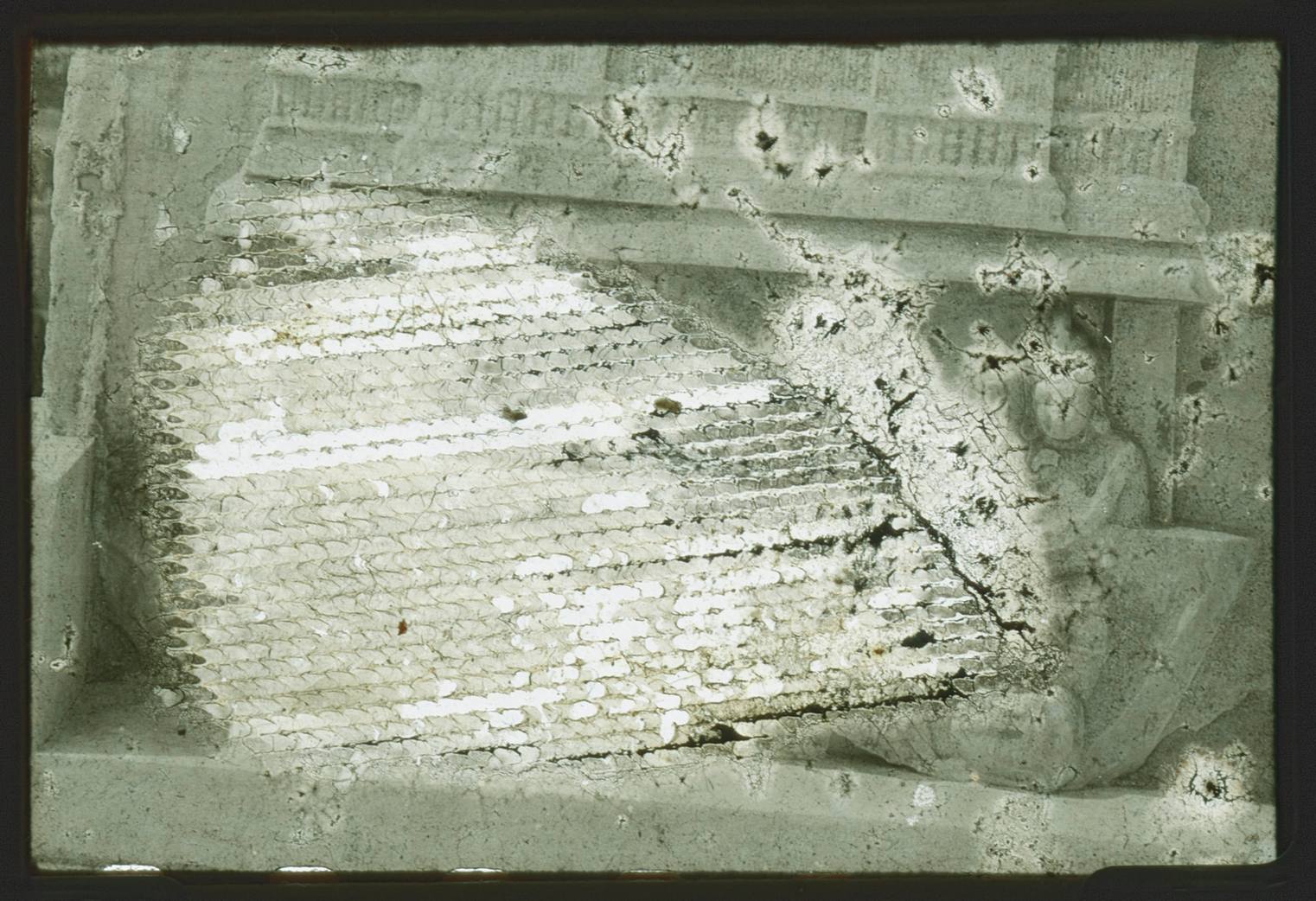

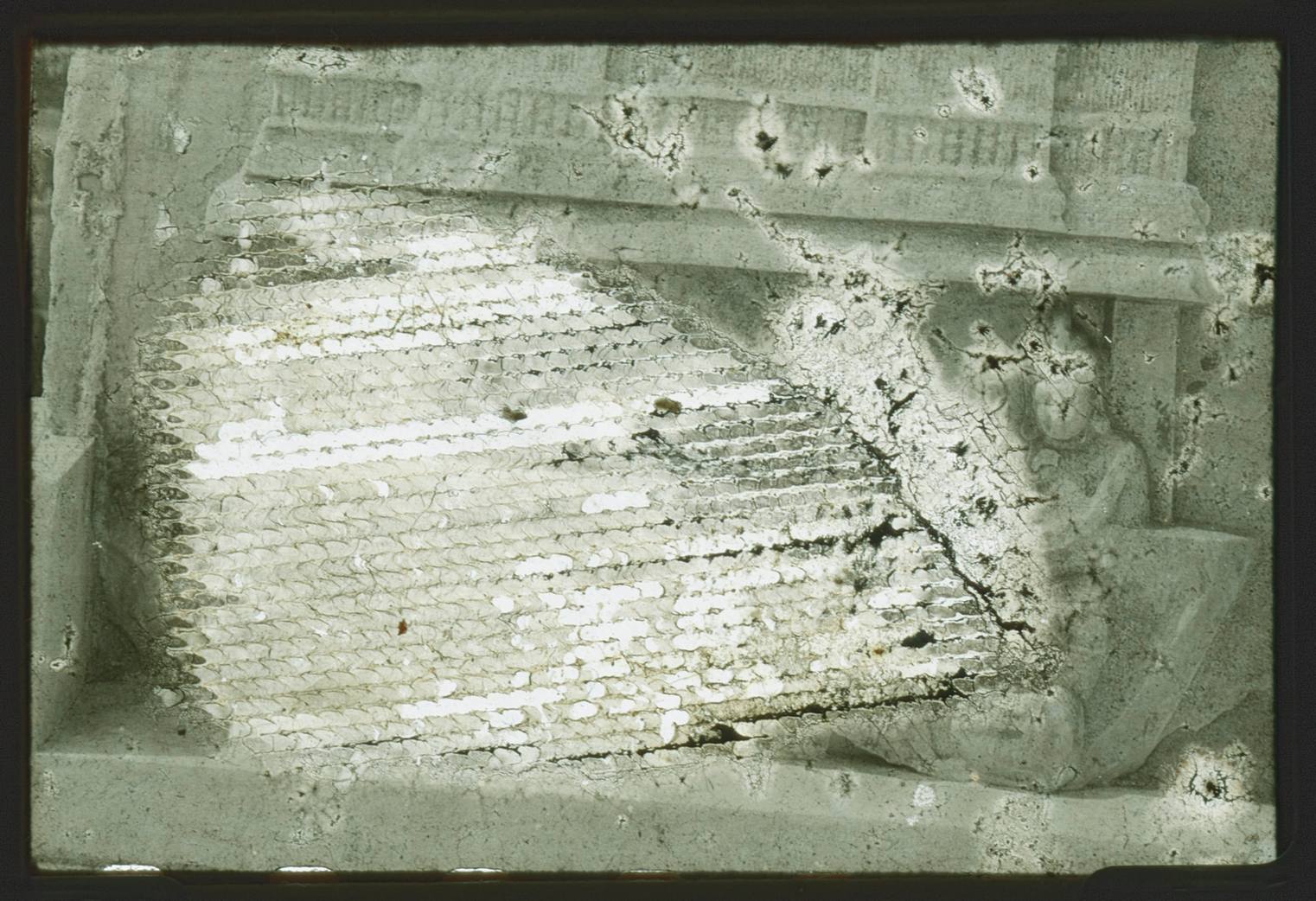

Somnath is widely applauded for the unique method of printmaking that was crystallised in the well-known ‘wound’ series. It started as a response to the Vietnam War and the socio-political unrest in Bengal by the late-1960s and 1970s. The historical trauma was expressed as incisions on the paper-pulp surface that Somnath made himself by transferring from a clay matrix. It contained of abstract impressions on paper pulp ground, evoking lesions on bodies, animate or otherwise. He is also known for his versatile handling of a wide range of mediums such as oil on canvases, drawings in watercolour and crayons, different methods and techniques of printmaking and bronze cast sculptures— a versatility that will be highlighted through the more than hundred works displayed at KNMA.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

K Ramanujam: Into the Moonlight Parade

23 March 2022 - 13 August 2022

The figure of the artist as an outcast with a personality that verges on insanity and self-destructiveness is a recurrent yet barely understood trope of modernist narratives. Today, with the withdrawal of modernism, this solitary figure has become only more obscure, romanticized, and even stereotyped. However, the ongoing pandemic that forced many into seclusion has inadvertently offered the opportunity to finally return to examining, with greater reflectivity and sensitivity, the missing pages of history. The mythopoetic universe of K Ramanujam (1941–1973) appears to be an impenetrable citadel watched over by the peering eyes of demigods – a nocturnal world shielded by “an army of muses” to use the artist’s own expression. Despite the encouragement that he received from his mentor KCS Paniker at the Government School of Arts and Crafts and later at the Cholamandal Artists’ Village (Chennai, Tamil Nadu), Ramanujam lived practically as an outsider because of his speech impediment and alleged schizophrenia. Born into a conservative Tamil Brahmin/Iyengar family in Triplicane, the middle school dropout sought solace in Chandamama (‘Uncle Moon’), a South Indian children’s magazine beloved for its Puranic stories and intricate illustrations. As an adult, driven away by relatives, the penniless art student slept on the streets surrounded by Tamil cinema posters and gigantic hoardings. He frequented film shoots in Kodambakkam, fascinated by the elaborate sets created for mythological dramas. Further enriched by the Vaishnavite symbolism and Alvar Bhakti poetry tradition that he may have encountered as a child, Ramanujam’s artworks processed these experiences in sublime forms, at an intimate scale and in a material execution minuscule and modest. Finding admirers worldwide even during the artist’s lifetime, these intricate works often feature Ramanujam himself lounging cheerfully in the processional tableaux, having created and now commanding a world mysteriously his own. In reality, however, the artist’s quest for love and dignity remained unfulfilled, pushing him to take his own life at the age of 33. Art had the power to both pull Ramanujam into, and rescue him from, the profound, alienating forces of darkness. In his haunting absence, KNMA attempts to present how Ramanujam’s deep wounds and intense passion for the world around him peopled his solitude and art. Paying homage to him with the first solo exhibition of the artist to be held outside his native state, we invite everyone to partake in the moonlight parade of K Ramanujam.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

Atul Dodiya: Walking with the waves

23 March 2022 - 13 August 2022

Exploration of the world outside, one which is rooted in the real, yet silently allowing the fantastic to enter the image-scape. So far, what had only been subjects of routine observances turned into remote recesses. What he had not realised was the power of the subconscious to dredge up, from the depths of the mind, extemporaneous views of trees, creepers, plants, sky, clouds, water bodies and waves of imagination.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

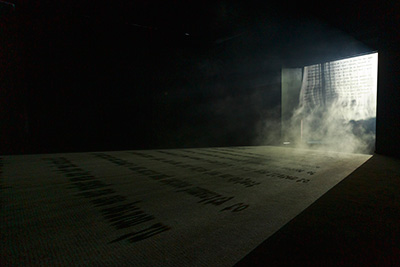

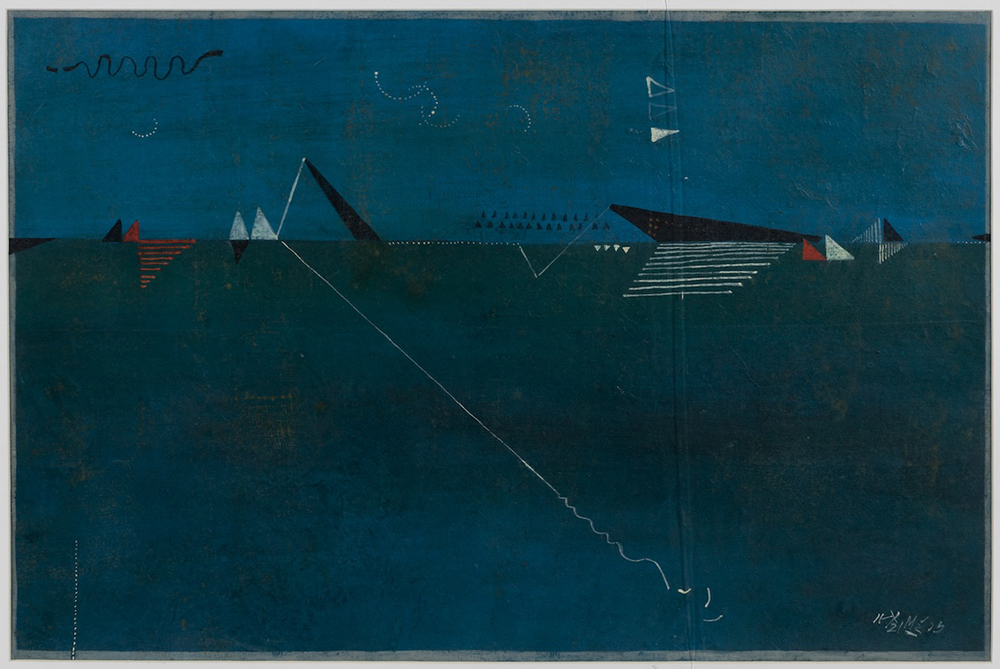

Zarina – A Life in Nine Lines

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Zarina: A Life in Nine Lines | Across Decades - Borders - Geographies is a solo show dedicated to the artistic career of Zarina Hashmi. Primarily exploring the medium of paper and her fascination towards it, the exhibition showcases woodcut prints, lithographs and etchings along with a few sculptural objects. Her life fraught with migration, fascination for architecture and symmetry and interaction with varied cultures influenced the themes, techniques and methods in her works. The trauma of Partition and pain of un-belongingness take complex existential dimensions, through a mystically elevated minimalism that takes history as its point of departure. Absorbing the intensity of longing to return to an origin, and transforming the desire into a poetically minimal visual language, Zarina conjured a world with the idea of ‘home/s’ which recall different times, places and emotional states. Home is often interpreted in the form of nostalgia, relations, geographies and place.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

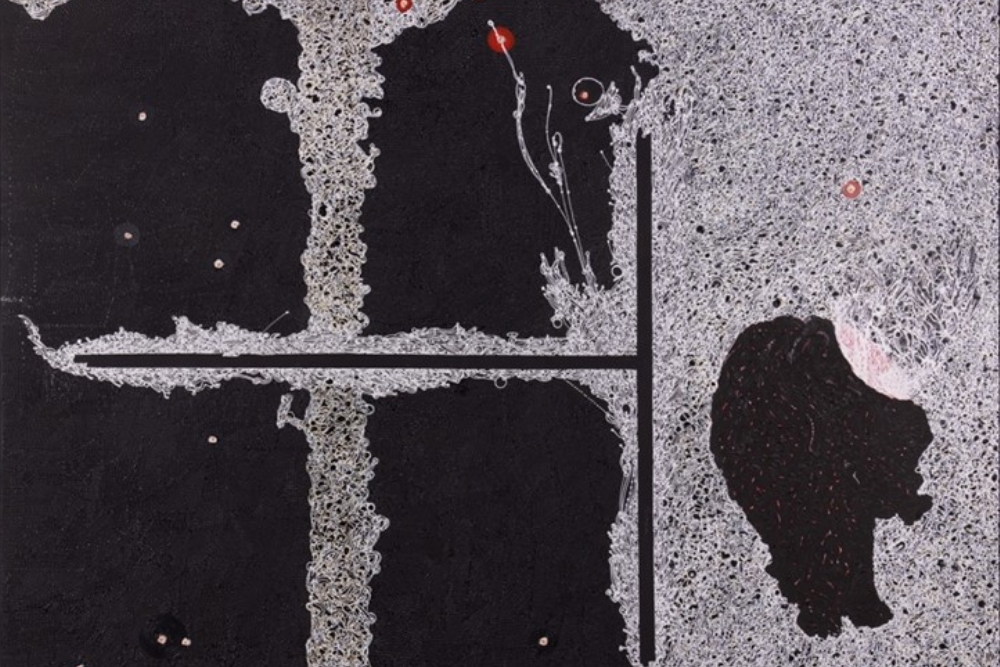

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

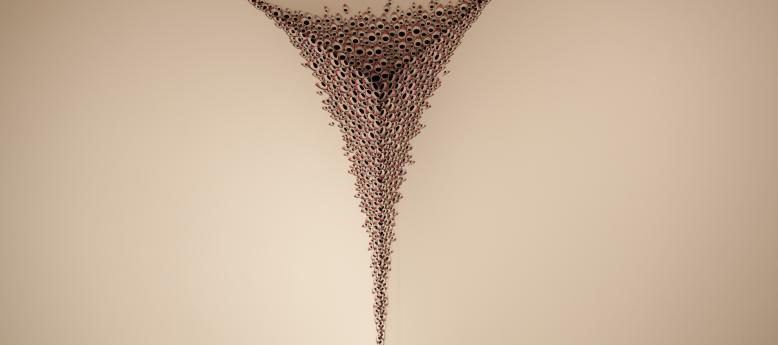

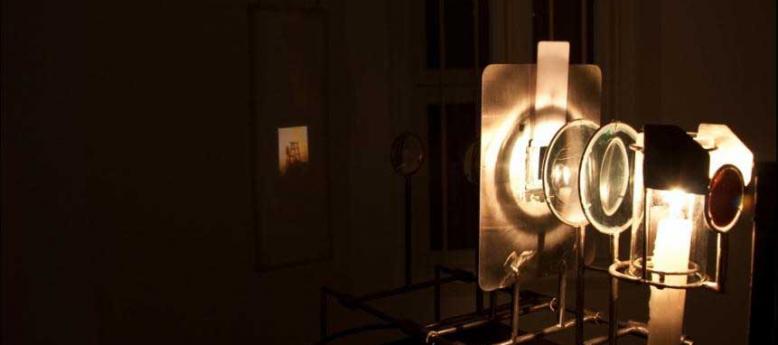

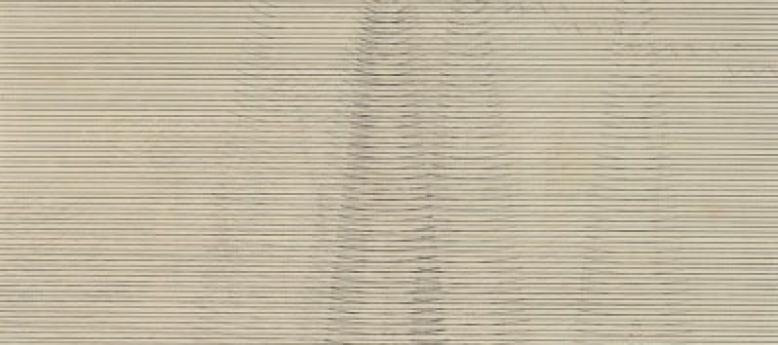

The show Line, Beats and Shadows presents artists Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh and their eclectic interpretation of abstraction. The artists use an array of material, often disguising it to appear in a different form. Ayesha Sultana masquerades fragile paper into metal, her aesthetics drawn from the visuals of Dhaka’s shantytowns marked by disparate class conditions. On the other hand, Prabhavathi Meppayil’s works of metal parts marked by an economy of means harmonizes modernist practices with traditional craftsmanship of goldsmiths in southern India. Sumakshi Singh uses the aspects of nostalgia and memory to recreate domestic architectural spaces using lace embroidery. In place of brick and mortar, the fragile space breathes a new life as people inhabit the space while engaging with spectral cob-webs of past memories. Encapsulating Lala Rukh’s parallel photographic practice are a suite of six works on display which were recorded during Lala’s travels across South Asia between 1992 and 2005. Laced with minimalism, a philosophy which she carries throughout her studio practice, each series of small works reflect time-captured tranquil topographical views of water bodies, devoid of people or beings.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

Abstracting Nature – Mrinalini Mukherjee and Jayashree Chakravarty

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

A mirroring of approaches is seen in the show Abstracting Nature as the artists Mrinalini Mukherjee and Jayashree Chakravarty amalgamate myriad objects found in nature into their own oeuvre. Seeking solace in the serenity of nature also deeply resonates with the artists’ philosophy. A corpus of drawings, etchings and watercolour produced by Mrinalini Mukherjee showcases the artist’s long standing connection with nature including her self-absorption in the flora and fauna in her immediate environment. A careful look at these works reiterates Mrinalini’s perception of nature- where cords, knots, tangles and twists become apparent as her unswerving preoccupation. In addition to these work, Mrinalini’s bronze piece and her hemp sculptures crafted by knotting jute ropes/ fibres into sculptural material through enormous muscle power, energy and time are displayed.

Over the last three decades or more, Jayashree Chakravarty’s art practice has addressed the exigent situation of shrinking natural habitat and water bodies in ever-expanding Indian cities. Jayashree through her works reminds us that the earth is continuously being pushed towards a precarious edge, where the threat of daily damage has taken on precipitous dimensions. Through poetic evocations, she weaves into her personal vision, the need for environmental balance and resurrection. Nature continues to be the subject as well as the substance of Jayashree’s art. Her works draw sustenance from the organic materials she puts to use, collecting dry leaves and dry flowers, twigs and delicate branches, roots and medicinal seeds, and now, crushed eggshells as well, weaving and mending, as if the ruptured fabric of life.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

A thought-form part of the Young Artists of Our Times series Devised by Akansha Rastogi

Kush Badhwar + Alexander Keefe + Vidisha Fadescha Anish Cherian + Simultaneous reading of Paul Lafargue's The Right to be Lazy and Aman Sethi's A Free Man

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

New Delhi, December 9, 2019: Iss ghat antar baag bagiche is an homage to Haku Shah (1934 – 2019), the reticent artist who grew up in an environment inspired by Gandhian thoughts and philosophy. We remember him as a painter, photographer, crafts archivist, an empath with a cultural polyphonic affection, well-known for his collection of artefacts of vernacular arts accumulated in the course of his extensive research and travels across India. Haku Shah meticulously documented varied cultural expressions of the rural arts and crafts, objects, techniques and processes of making. Drafting almost a new form of practice in post-independent India, with a strong educational focus. A cultural anthropologist with an archivist’s zest and values, his contribution to the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, Shilpa Gram in Udaipur and several path-breaking exhibitions, remains unique. Mentored by artist-pedagogue KG Subramanyan, Sankho Chaudhuri and NS Bendre at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda, Haku Shah’s artistic passage, sought and created harmonious relationship between object, technique and concept.

Around eighty works from the Haku Shah archive including paintings, terracotta sculptures, textile scrolls, books, journals and periodicals will be displayed in the exhibition. Moving between miscellanea of mediums from oil on canvas, mix media collages to colour pencil and ink drawings on postcards to Shah drew from an assembly of cultural references. From 15th century Bhakti and Sufi poetry and verses to more recent literature, music, creative and social expressions the works carry a gamut of both dynamic and dormant avenues for interpretation. The exhibition brings together works from several series and a few that are being exhibited for the first time. It includes his collaboration with musician and vocalist Shubha Mudgal which resulted into the exhibition Haman hain Ishq (2002), the other series being Noor Gandhi Ka Maeri Nazar Main(1997), Nitya Gandhi / Living Reliving Gandhi (2004) and Maanush (2007) that reflects on humanism, embodiment and disciplined pursuit of Gandhian values and processual politics.

Born in the village of Valod, Gujarat to Vajubhai and Vadanben Haku Shah grew up in a region that imbibed a nationalist fervour and propagated the Gandhian way of life, having being located near a Gandhi ashram and centres of Satyagraha in a pre-independence scenario. Shah pursued his education from the Faculty of Fine Arts; Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda 1955-59. He had begun drawing at a young age, copying portraits of Gandhi in tune with the nationalist trends. The interdisciplinary and free atmosphere at Baroda initiated a foundation for his larger practice. After completing his fine arts degree in Baroda, Haku Shah taught at a Gandhian Swaraj ashram, Vedchhi in Surat district of Gujarat, and since then the handspun yarn became an important expression of his artistic persona. Dr. Stella Kramrisch invited Shah to curate the seminal exhibition “Unknown India” while he was associated with the National Institute of Design (NID) in 1967. The tribal museum at Gujarat Vidyapeeth in Ahmedabad, which was founded by Mahatma Gandhi, was a site Shah engaged with. He taught at the School of Architecture, Ahmedabad for many years, aside being Regent Professor at University California, Davis. An awardee of honours like Padma Shri, Kala Ratna, Kala Shiromani, Gagan Abani Puraskar and fellowships like the Rockefeller Fellowship and the Nehru Fellowship, Shah implemented a parallel modernity, inspired by vernacular philosophies.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

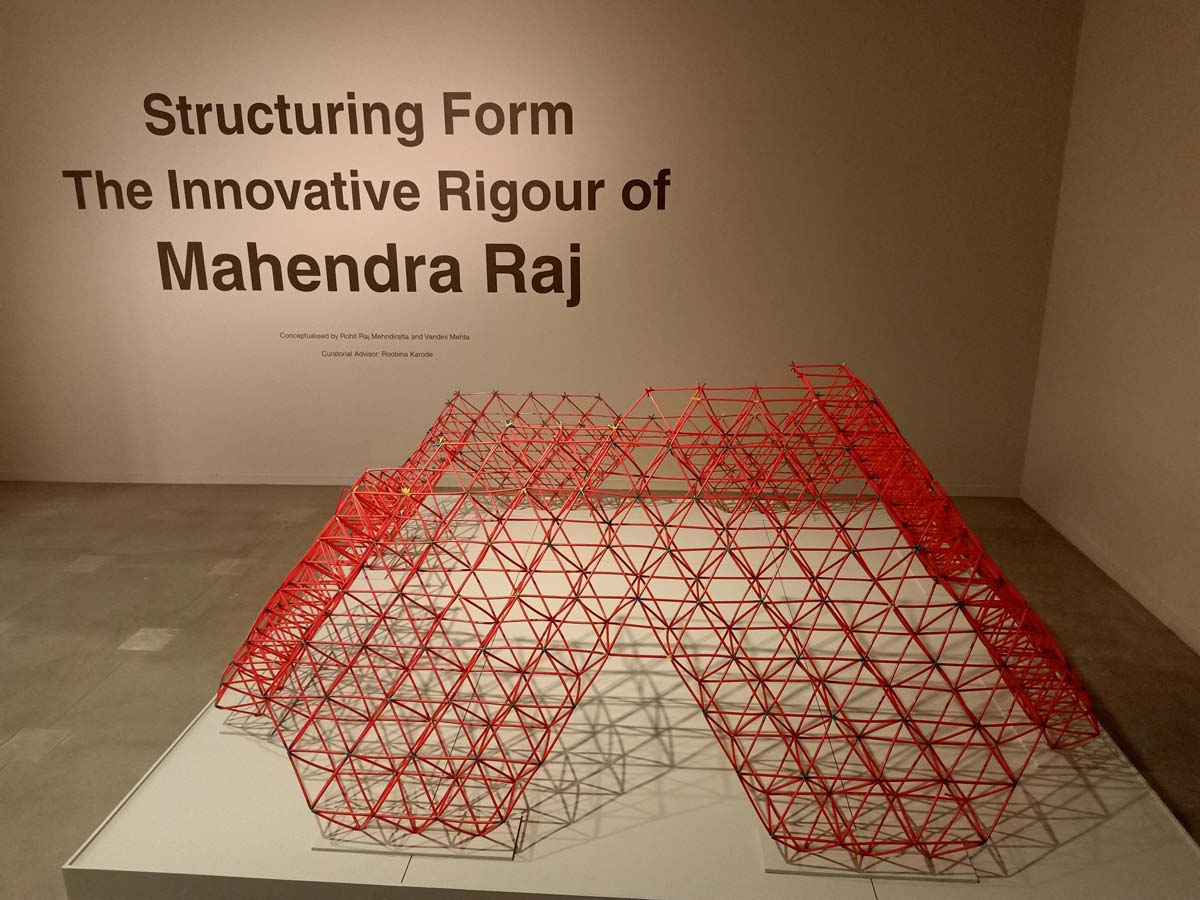

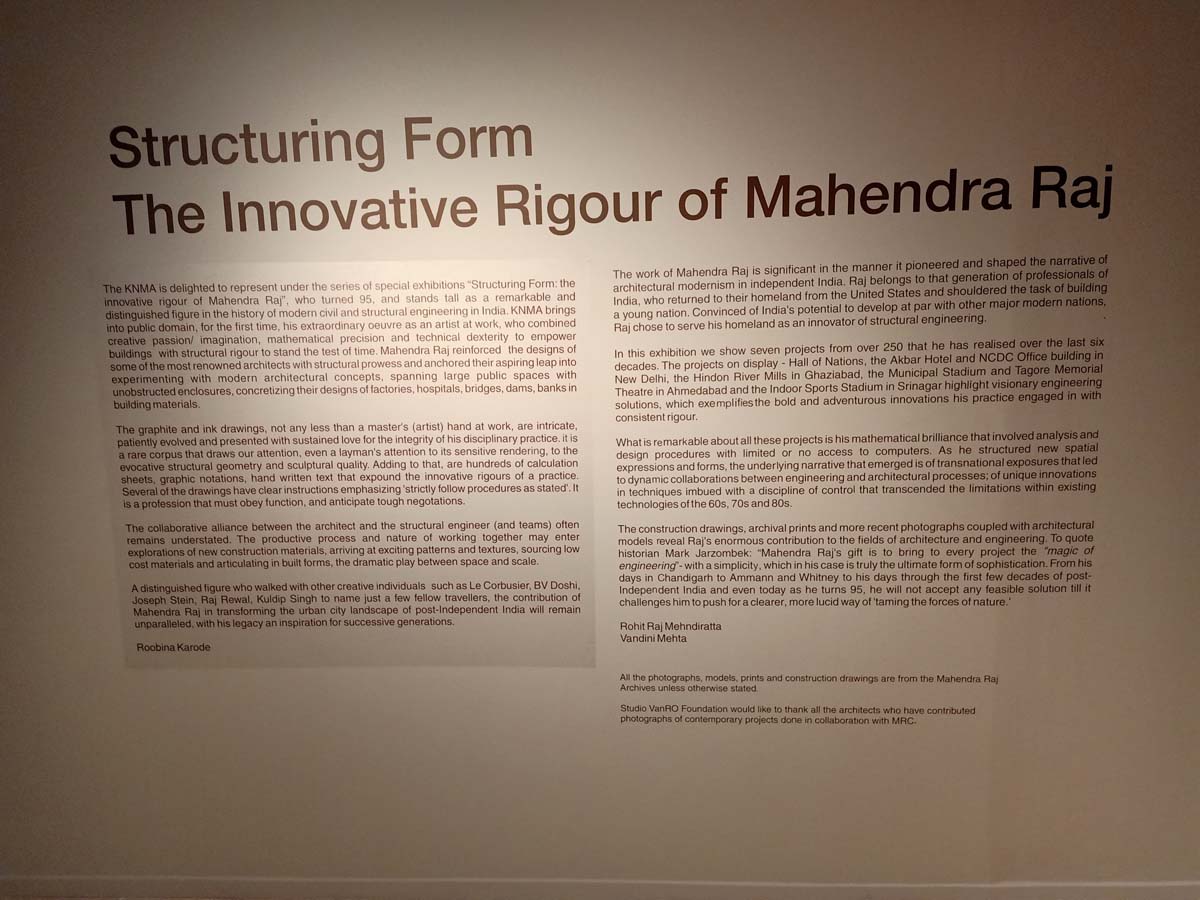

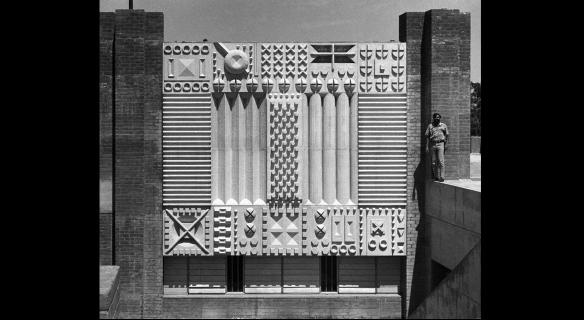

Structuring Form

The Innovative Rigour of Mahendra Raj

19 November 2019 - 8 January 2020

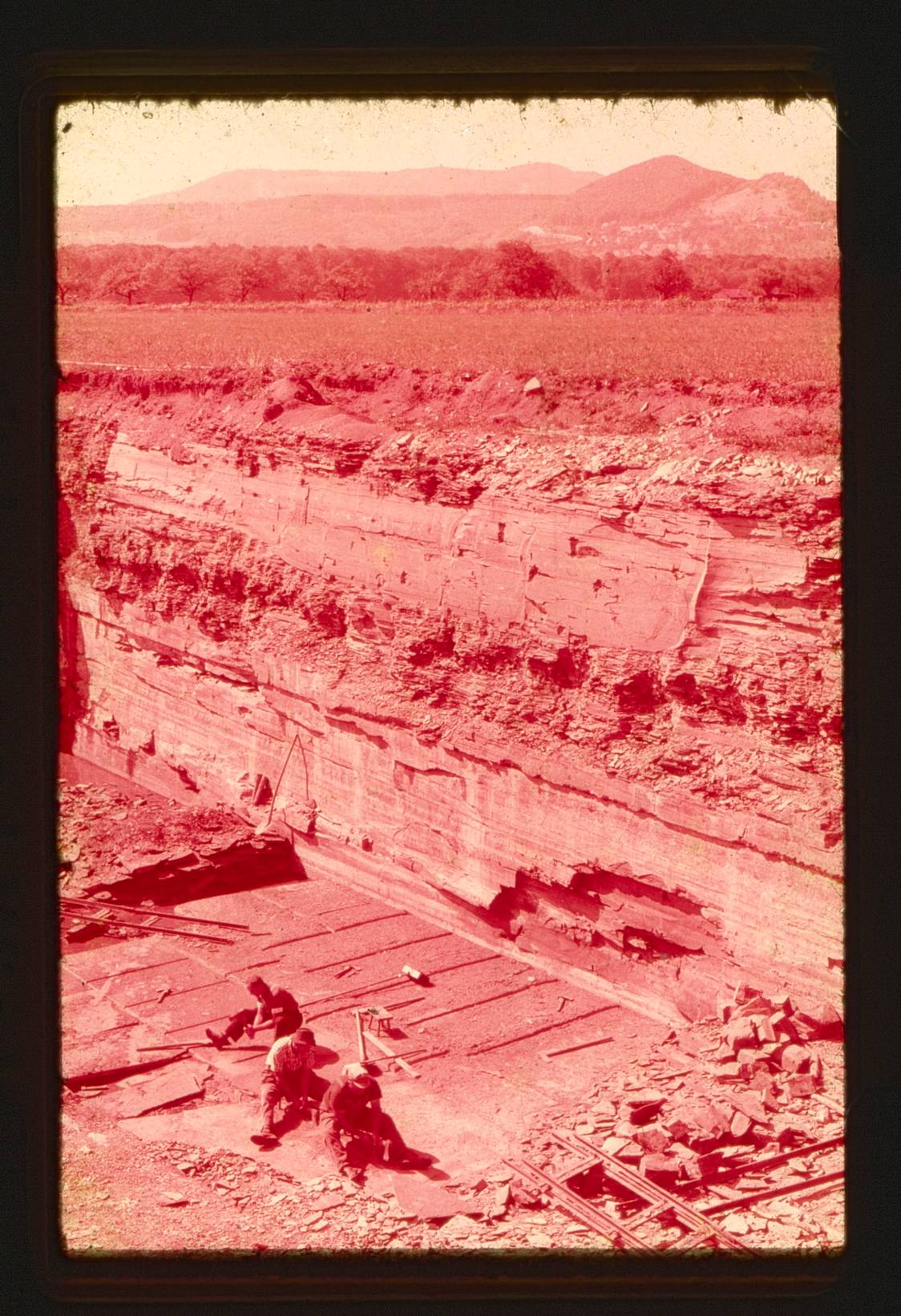

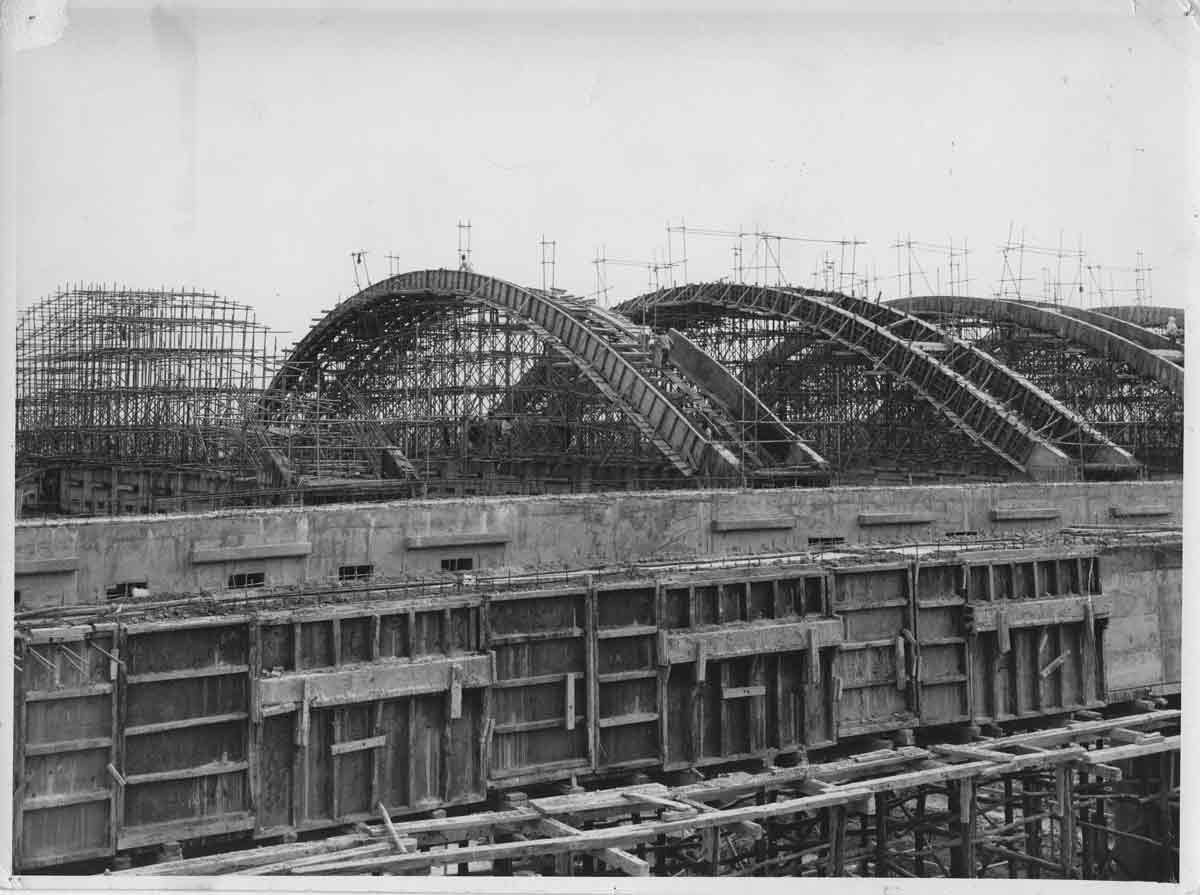

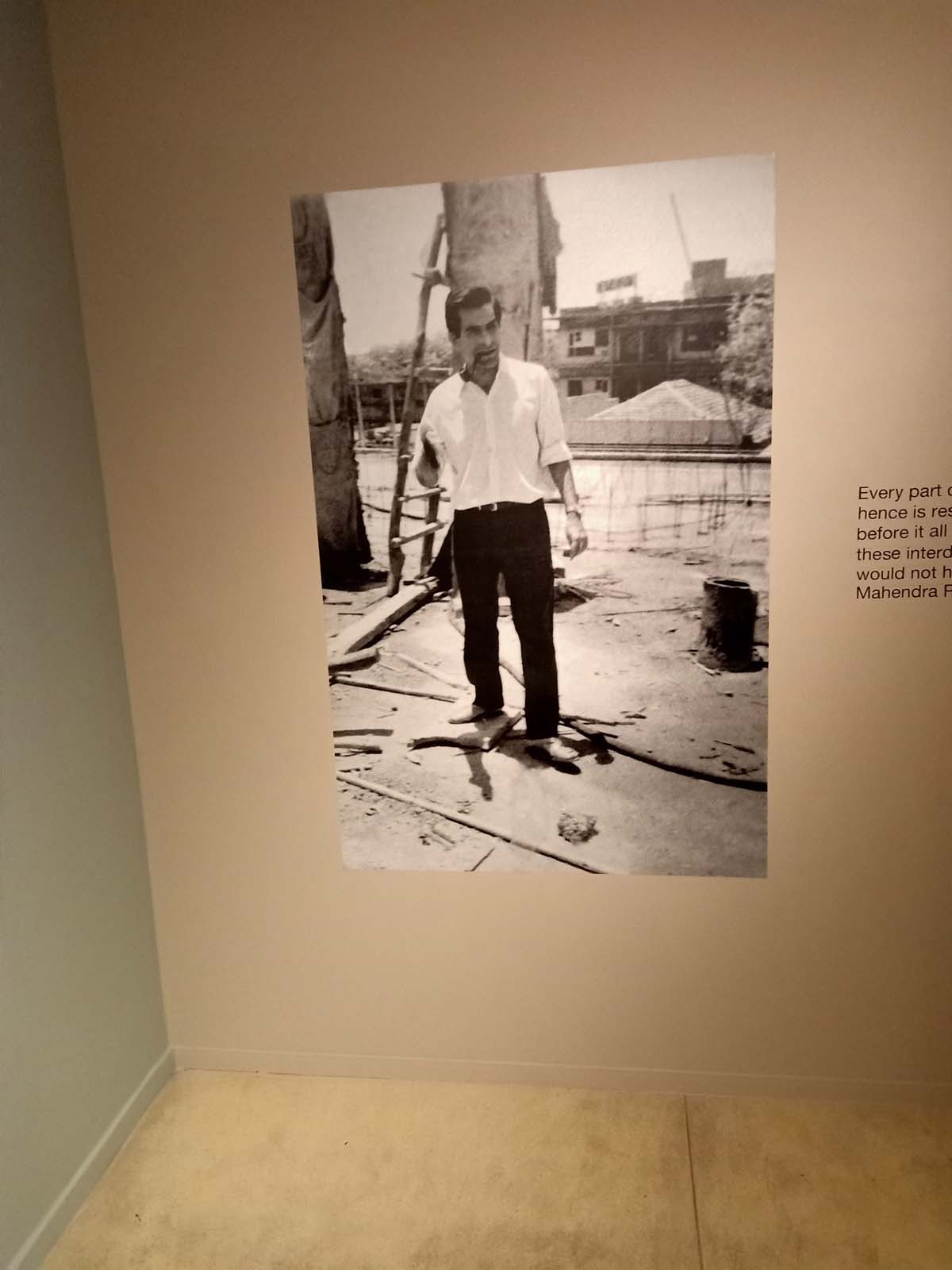

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art is pleased to announce a special exhibition detailing seven architectural projects, raised by the structural engineering genius of Mahendra Raj out of his two hundred fifty projects. The collaborative alliance between the architect and the structural engineer (and teams) often remains understated. The productive process and nature of working together may enter explorations of new construction materials, arriving at exciting patterns and textures, sourcing low cost materials and articulating in built forms, the dramatic play between space and scale.

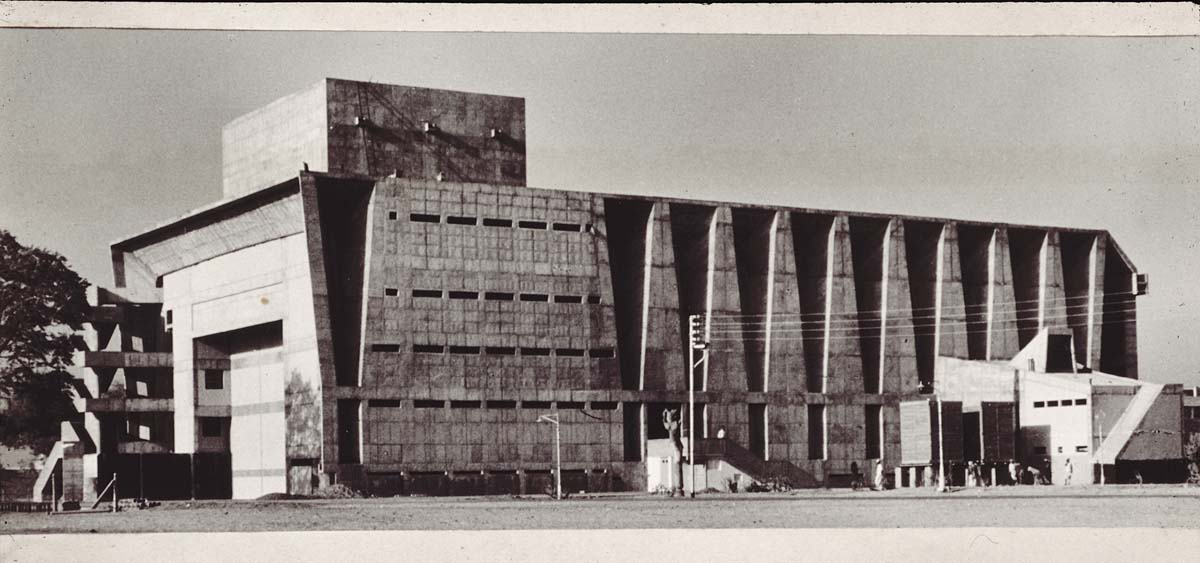

The projects like the Hall of Nation in New Delhi, the Akbar Hotel and NCDC Office building in New Delhi, the Hindon River Mills in Ghaziabad the Municipal Stadium and Tagore Memorial Theatre in Ahmedabad and the Indoor Sports Stadium in Srinagar find special place in this exhibition, alongside chronicling the career of this engineering innovator.

Architects like Charles Correa (Municipal Stadium, Ahmedabad), Raj Rewal ( Hall of Nation), BV Doshi ( Tagore Memorial Hall), Kuldeep Singh (NCDC Building) are considered hallmarks of modern India architecture. It was arguably their partnership with a Structural Engineer like Mahendra Raj that phenomenal modernist architecture found space on the developing Indian terrain. Mahendra Raj’s career can be mapped altogether the period of India’s Post-independence modernisation, a period marked by massive constructions flourishing across the country, that eventually changed it’s urban landscape.

The ambition of a budding nation like India was marked by widespread building of structures like stadia, theatres, bridges, dams, factories, airports, hospitals, universities and banks. The first prime minister of Independent India Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru hailed modern industrial buildings as the new age temples of modern India. Throughout the several ups and downs witnessed by the Indian economy over the decades, the developmental work that entailed a nation’s infrastructure was distinguished by recruiting a resourceful, avant-garde pioneer like Mahendra Raj.

Concrete as building material was popular across the world, when Mahendra Raj executed these structures, however the material had its own limitations. In the 1960s, India was far from intense mechanisation unlike the western countries, Raj used this shortcoming to his advantage and experimented with structures, with the availability of affordable material and labour.

“Mahendra Raj has carried the whole modern Indian architecture on his shoulders. My interaction with him was like a jugalbandi that has helped enhance and execute my visions”, mentioned Raj Rewal[1], while describing the immense skill and tenacity with which Raj, executed these magnificent structures. Mahendra Raj’s ingenuity lay in the fact that he deployed easily available manual labour as well as construction material to craft his structures almost like artefacts, so unique that they went on to become his signature aesthetics.

His life and work garners much more relevance and attention in present times with the growing threat of demolition of modern structures like the iconic Hall of Nations, one of the featured projects in the exhibition, was razed to dust in 2017. The archive of his structures along with recent photographs indicate the power and elegance of different structures as they were constructed and laying bare the engineering inventiveness of Mahendra Raj. The drawings, especially the blueprints reveal the ‘techne’ of construction in different decades of Raj’s practice. These buildings were iconic objects, many with a commanding presence and setting, compelling one to look upon him as a craftsperson, even artist-visionary of his times and after.

[1] From the book ‘The Structure, Works of Mahendra Raj’, 2016, edited by Vandini Mehta, Rohit Raj Mehndiratta and Ariel Huber.

Other Exhibitions

visions of interiority: interrogating the male body - A RETROSPECTIVE (1963-2013)

14 October 2014 - 1 March 2015

You can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag - A RETROSPECTIVE (1969 - 2014) in three chapters

26 September 2014 - 21 December 2014

A view to infinity - A Retrospective (1937-1990) Part of Difficult Loves

31 January 2013 - 8 December 2013

the dark loam: between memory and membrane - A RETROSPECTIVE (1930-2016)

24 August 2016 - 20 December 2016

The euphoria of being Himmat Shah A continuing journey across six decades

30 October 2017 - 15 December 2017

VIVAN SUNDARAM, A RETROSPECTIVE: FIFTY YEARS STEP INSIDE AND YOU ARE NO LONGER A STRANGER

9 February 2018 - 20 July 2018

Envisioning Asia, Gandhi and Mao in the photographs of Walter Bosshard

1 October 2018 - 31 October 2018

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art presents इस घट अंतर बाग-बगीचे | Haku Shah 1934-2019 Within this earthen vessel are bowers and groves

10 December 2019 - 8 January 2020

Right to laziness... no, strike that! Sidewalking with the man saying sorry

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Line, beats and shadows – Ayesha Sultana, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Lala Rukh and Sumakshi Singh

30 January 2020 - 10 April 2021

Delhi Modern: The Architecture of Independent India seen through the eyes of Madan Mahatta

13 February 2020 - 28 February 2020

Around The Table : Conversations about Milestones, Memories, Mappings

5 November 2022 - 22 December 2022

Prussian Blue: A Serendipitous Colour that Altered the Trajectory of Art

19 September 2023 - 20 December 2023

_0.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)